When you write a book about someone you enter into a relationship with them, even if they are dead and the relationship is imaginary. It continues to exist after the book is published, the promotional work is done, and you have moved on to something else. You cannot, it seems, easily discard it – any more than you can easily discard a friendship that may have run its course. These connections endure within. They claim a lasting part of one.

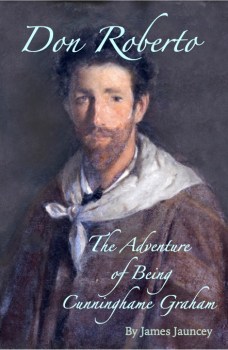

I am trying to let go of my great-great-uncle, whose biography I published two years ago, and about whom I have written here often; probably too often. I wrote the book in the first place as a kind of exorcism. He had been part of the backdrop to my life for sixty years and I needed to understand why. What was the hold he had on me, and, much more powerfully, on my mother before me?

The book went some way to answering the question, by helping to explain what he represented to my mother, for whom he was a lifelong hero and role model; and to me, at a remove of three generations, as an almost mythical if two-dimensional figure whose real, complex human character began to emerge as I wrote. To get to know something is to take away some of its power over you.

But ten years since starting to write the book he is still more present in my life than I would like him to be. He is still there a little like a hangnail, and I have only myself to blame. A year ago I agreed to become chair of the society that exists to promote him and his work. In recent months we have put a lot of time and effort into creating a website, reviving a newsletter, organising events and promoting membership.

Today we have an afternoon symposium at Glasgow University about his travels and writing, his wife’s no less extraordinary life, and his progressive (for the turn of the 20th century) views on women. I am due to speak about his travels, and I am not the first to be struck by the fact some of his best writing is about journeys that ended in failure.

There are three of these in particular. In the 1870s, in his mid-twenties, adventuring in South America, he made an attempt to buy horses in Uruguay and drive them north for sale to the Brazilian army. The horses drowned in rivers, died of snake-bite, went lame, or fell ill, and he was eventually halted by a tract of impenetrable forest beyond which, he was told, the pasture was poisonous.

The second came in his early forties when, beset by financial difficulties, he read in an edition of Pliny about a Roman gold mine in a remote part of northern Galicia. After days of arduous travel and back-breaking panning, he departed with a sack of dust.

The third and most dramatic, a few years later, was his attempt to reach the city of Tarudant in southern Morocco, forbidden to foreigners at a time of political turmoil in the country. Disguised as a sheikh, with a Berber guide and a Syrian interpreter, he was captured while crossing the Atlas Mountains and held for three weeks by a local warlord.

At a time in our imperial past when tales of Britons abroad were generally triumphant in tone – the longer the odds, the more treacherous the terrain, the wilier the natives, the better – he was not only writing candidly about his own lack of success, but with empathy and real understanding for the people through whose lands he passed.

At the conclusion of the story of the Brazilian adventure he writes:

Had but the venture turned out well, no doubt I had forgotten it, but to have worked for four long months driving the horses all the day through country quite unknown to me, sitting the most part of each night upon my horse on guard, or riding slowly round and round the herd, eating jerked beef, and sleeping, often wet, upon the ground, to lose my money, has fixed the whole adventure on my memory for life. Failure alone is interesting.

He has since been mis-characterised as having either glorified failure, or been ashamed of it. I don’t believe that is the case at all. Rather, that with his endless curiosity about human nature, he found it more rewarding to write about what is flawed than what is perfect; and with his storyteller’s instinct he recognised that in conflict and challenge, in the possibility that things will not end well, whether or not they actually do, lies the essence of every good tale.

Our propensity to fail is a defining characteristic of our humanity. In failing to let go of him, or at any rate to smooth away the hangnail and let him settle less insistently into my consciousness, I may simply be reminding myself of that, and have to accept that for the time being he’s still with me.

Wonderful ( – not an exaggerated word, in this rare instance!) and multi-dimensional tract, as always…..I admire without end the ‘double-layered’ approach of binding philosophical discoveries and analysis together with dramatic life-line narrative! – By way of a single instance, the comment, ‘ To get to know something is to take away some of its power over you’ – says it all in respect of my objective of highlighting the double-layered approach to life, to narrative and to explanation / interpretation! The extreme visual scenes of horses in Brazil, beef-jerky, and equine expiry, for example, begins to say it all – an underlying motivation – subconscious, perhaps? – which sort-of says it all, to repeat – intentionally! – my ‘words of praise’…..Allelujah! – to be interpreted by way of laudable acknowledgement however anyone may see fit!. Thanks so very much.

LikeLiked by 1 person